by Van K. Tharp, Ph.D.

October 17, 2018

A note to readers: While Dr. Tharp’s content is timeless, this article is from our newsletter archive and may contain outdated information, missing links or images.

In my experience, I find that it is very easy to design a system that will produce great returns (even 100% or more). What’s difficult is actually trading the system and getting those returns. In this article, I’ll show you how easy it is to develop a great system, how mistakes can be your downfall, and how to correct the mistakes you make.

Thinking of Your Results in Terms Risk-to-Reward

One of my fundamentals of trading success is that you must have a predetermined exit point before you enter into a trade. This exit point represents your worst-case risk in that trade. Let’s call risk, R, for short, and look at a few examples.

Suppose you decide to by something at $40 and sell it if it drops 10% to $36. Your risk in this case is $4. If you are buying stock, it means your risk is $4 per share. Now suppose you have $100,000 in equity and want to risk 2% or $2000 in this trade. This means that you can afford to buy 500 shares of stock (i.e., divide your total risk of $2000 by your per-share risk of $4 and you get 500 shares). Notice that you would be buying $20,000 worth of stock, but that your initial risk would only be 10% of that (because of your 10% stop) or $2,000. I’m not recommending any of these numbers (i.e., 10% stops or 2% risk); I am merely using them as examples.

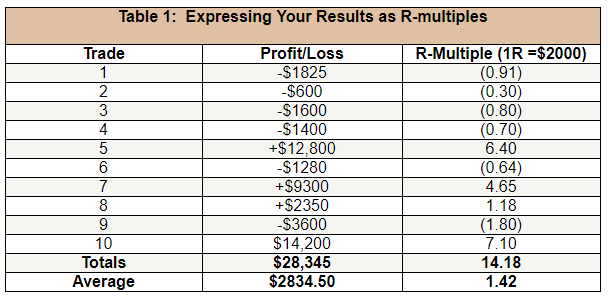

Let’s look at some more examples. Suppose you have a $200,000 portfolio. You want to buy 10 stocks, each with a 1% risk and a 10% stops. You can do that and you will be fully invested. Now suppose that you have bought those positions and you get the following rules as shown in Table 1. The table shows the profit and loss on each position and then expresses the result as a multiple of the initial $2000 risk. This is an example of presenting your results as R-multiples.

There are several key things you should look at in this system. First is the expectancy of the system, which is the average R-multiple produced by the system. In this instance, the expectancy is 1.47R. When your sample is large enough, and this means 30 to 100 examples, then your expectancy will also tell you what you can expect to make, on the average, over a large number of trades. Half of your results will be above the expectancy and half of your results will be below the expectancy, but on the average over many trades your results should equal the expectancy.

Let’s say that your expectancy over 100 trades is 1.5R and that your system produces about 60 trades per year. Under those conditions, you might expect to make about 90R (i.e., 60 times 1.5R = 90R) per year. And if you risked 1% of your total current equity on each trade, then you could easily make 100% per year.

“But wait,” you say, “this is really stretching things. For example, 90R is the average return you might get, but half the time the return will be better and half the time the return will be worse.” Well, my response to that statement is that 90R per year is a reasonable result for a good system. In fact, I’ve seen many systems results that are much better than the results in this example. A system that could deliver a return of 100% per year is not that difficult to design.

Remember that we are now thinking in terms of R-multiples. A 10R gain now means that you only have to make 10 times your risk, not 10 times your investment. And since your risk was only 10%, it means that if we double our investment, we have a 10R. And in my experience, it is not that difficult to develop a system that has occasional gains of 10R or more. The big problem is that most people, once they have developed such a system, cannot trade it effectively.

Why Isn’t Everyone Making These Returns?

Because people make mistakes. The average person will never achieve anywhere near the expected return from their system because they make mistakes. So what is a mistake? My best definition of a mistake is not following your rules. For people who don’t have any written trading rules, then everything they do is a mistake. So let’s look at some common mistakes. These are mistakes that I see professional traders make (not just the average person) all the time.

- Not taking a trade that is signaled by your system because you are afraid, not automated, or just are not paying attention.

- Taking a trade because of emotions or excitement or just not realizing it.

- Keeping a mental stop and then letting the price run right through it.

- Trading several systems at the same time with conflicting results and doing it in the same account.

- Having position sizing that is too large. 2% is pretty risky, but sometimes people risk 5-10% or more).

These mistakes are very costly. Our preliminary research suggests that an average mistake is worth about 4R. I don’t know if that number will stand up over many, many examples, but that’s my current best guess for the value of a mistake. So what if you make two such mistakes each month? That means you are making 8R worth of mistakes every month. Again, I don’t know how many mistakes the average trader will make, but I do know that the more active you are, then the more mistakes you will make.

If your mistakes add up to 8R each month, then you are making 96R worth of mistakes each year. And if we apply it to the original example I gave, in which your system makes 90R per year, you have a net result of negative 6R. Thus, you’ve now turned a winning system into a net losing system by your mistakes. And what usually happens is that you decide that your system is broken and stop trading it. But the system is perfectly fine; it is just your mistakes that are the problem.

Notice that you are making 60 trades each year and about 24 mistakes. In terms of mistakes, we might say that you are 60% efficient. But in terms of results, you are in the hole, so we’d have to call you totally inefficient.

Mistake Examples

One of the keys to correcting mistakes is to recognize them. For example, I sometimes play a marble game at talks. Marbles are pulled out of a bag, each representing a different R-multiple of a trading system. Each marble is replaced after it is pulled. The expectancy of the game is 0.8R and usually we do 30 trades. That means that everyone should be up (on the average) 24R at the end of the game. However, when starting with $100,000, I’ll see a third of the room go bankrupt and another third of the room lose money because of position sizing mistakes. For example, if you risk it all on the first trade and you get a 1R loser, then you are bankrupt. You cannot play any more and have no chance to get the 0.8R expectancy.

But what do most of these people say when they play the game? First, we have the justification response: “This isn’t like real trading; it’s just a stupid game.” Next, we have the guilt response: “I was a stupid idiot.” And last, we have the most common response, the blame response: “I lost money because the marble pull was bad and that guy pulled out a losing marble for me. I’m just unlucky.”

In this instance, most people don’t even recognize their mistakes because they are blaming, justifying, or putting themselves through a guilt trip. Yet the mistake, of course, was that they went bankrupt because they bet too much on the marble pull. And if you don’t recognize your mistake, how can you correct it? You cannot. Instead, you’ll probably repeat it until you give up.

Let’s look at another example that represents real life trading. Let’s look at a fictional trader, Morgan Green. She has a system that produces 100R each year, but makes a lot of mistakes that she doesn’t recognize. Let’s look at a few examples of her mistakes.

- She hears a stock recommendation on the television, gets excited about the stock and buys 1000 shares. She loses money. What’s her mistake? In this case, she didn’t follow her system. Instead, she bought impulsively based upon her excitement and her ability to be influenced by outside sources.

Morgan blames the guru on television for the mistake and as a result, doesn’t recognize her own mistake. This is an even bigger mistake and as a result there will always be another analyst on the television that she can blame for his bad recommendations. Here is the key principle: When people don’t recognize their mistakes, they are doomed to repeat them until they recognize them.

Morgan subscribes to several newsletters. She reads each of them and then picks several stocks to buy. She spends $20,000 on these stocks and they all sit in her portfolio and slowly go down. After a year, she is down $2000. And Morgan has missed many good trading opportunities because her account has these losers.

Morgan now cancels all of her newsletters, thinking that none of them are any good because she didn’t make money. But one of them had excellent returns if she’d taken all of the recommendations. However, she only decided to take certain recommendations—the ones that excited her. So then she thought it was the newsletter editor’s fault that she lost money.

Notice all the mistakes she made here.

- She only picked stocks because of excitement rather than treating each newsletter as a system and taking every trade.

- She blamed the newsletters for the mistake.

- She held stocks that were doing nothing, missing many opportunities to buy better stocks because her account was fully invested.

- And lastly, she didn’t recognize any of her mistakes, so she can easily repeat them (and likely will).

And here is another common mistake that I see all the time.

- Morgan’s system produces eight losses in a row, which is quite common even in a system that makes money 50% of the time. However, Morgan becomes afraid and stops taking trades. When she stops trading, she misses a 25R winner.

Later, Morgan starts to study the market again and she notices the big winner she missed. Her reaction is to say, “Oh, I’m a stupid idiot. My system signaled that trade, why didn’t I take it?” So Morgan is now getting into self-blame and she’s again missing her key mistake. When you recognize your mistakes, you can take the steps that are necessary to correct them. Calling yourself “a stupid idiot” does nothing to correct the mistake.

I could go on about the types of mistakes that people make. Perhaps you have recognized yourself in some of the examples. The main point is that people make lots of mistakes, which prevent them from doing well and getting great results from good systems. And this is not just the average trader. We are talking about many professional traders as well.

The Solution: One of the 10 Tasks of Trading

I’ve been modeling successful traders over the last 25 years. And out of that research, I’ve developed the 10 Tasks of Trading, which is a part of the Peak Performance Course. Most of those tasks will help you with correcting mistakes, but one of them in particular, the daily debriefing, is designed to help you fix mistakes.

The daily debriefing requires about five minutes at the end of the trading day. Think about what happened during the day and look at your written trading rules first. Also remember that if you don’t have such rules, then you are not ready to trade and everything you do might be considered a mistake.

The next step is to ask yourself one simple question, “Did I follow my rules?” If the answer is yes, then simply pat yourself on the back and go home (or if you are home do something else). You are done. And if you lost money and followed your rules, then you might pat yourself on the back twice.

But what if you made a mistake by not following your rules? What you now do is simply make sure that you don’t do it again. This requires looking for the conditions that produced the mistake, figuring out some solution to make sure you don’t repeat the mistake, and then mentally rehearsing that behavior until it becomes second nature to you.

Repeating the same mistake over and over again is what I call self-sabotage and that’s an entirely different issue. But your job as a disciplined trader is to make sure that you continually correct each mistake so that you NEVER repeat it.

So let’s go over the rehearsal process. What you need to do is discover the conditions that lead to the mistake. Next, you want to anticipate how those conditions might occur again. For example, let’s say the mistake is that you listened to some investment advice on television. How can you prevent that from happening again?

First, the conditions that lead to the mistake were:

- Watching the financial channel during the day.

- Not controlling your mental state so that you were excited by the financial advice you heard.

Preventing the mistake might simply amount to avoiding both of those conditions. First, you could resolve not to watch television while you are trading or at least turn off the sound. Second, think about making a checklist that must be filled in before you purchase anything. The checklist will consist of your buying criteria, which will probably not be met by some guru’s recommendation on the television. And your last resolution is to never again take a trade without filling in the checklist and making sure that all your criteria are met.

Your next step is to rehearse your solution. This makes your actions automatic so that you don’t have to think about it. For example, you could imagine yourself filling out numerous checklists in your mind. You could imagine yourself turning off the television or hearing the words “STOP” very loudly in your mind if you reach to turn on the television during the day. You must do each of these things a number of times in your head until both of them become automatic for you.

Do a regular daily debriefing and pretty soon you’ll find that your number of mistakes drops dramatically. My guess is that you’ll eliminate most of your mistakes within a few months. But if you stop your daily debriefing, you may find that your mistakes again start to occur. But that’s another example of self-sabotage and that’s another story.